One of the most important tasks faced by hardware developers is choosing the right operating system “flavour” to run. While for many vendors selecting Android is a no-brainer due to its open nature and popularity, inside its ecosystem there are a number of different firmware builds to choose from.

The device’s firmware, also known as ROM (read-only memory), defines how the user will interact with your device, as well as what features will be available both to the developer and the consumer.

In addition to the “official” open-source Android ROM known as AOSP (Android open-source project), there are quite a few ROMs, built mostly by enthusiasts, that differ from the original in a variety of ways. Custom firmware could be optimised to run on older and less powerful chips, to be focussed on the security and privacy of the users, or to allow for deeper customisation, and so on.

We’ve taken a closer look at a few open Android firmware projects that everyone can modify and use to power their own hardware.

This article is a part of a bigger guide about Embedded Android that intends to cover a broad set of topics about using Android as a platform for embedded devices.

CyanogenMod

Arguably the most well-known Android-based custom firmware, CyanogenMod has travelled the path from yet another open-source ROM developed by a few enthusiasts to a piece of software with a company behind it, which profits from contracts with hardware vendors.

Developed by Steve Kondik, aka Cyanogen, in 2009, the ROM was initially an enhanced version of another piece of custom firmware, and only worked with HTC Dream (known as T-Mobile G1 in the US). It gained significant popularity among the enthusiast community, with more developers joining the team in the following months. Since then, the user base of the firmware has been growing steadily.

The latest stable version of the AOSP-based CyanogenMod is built upon Android 6.0.1 Marshmallow, though it’s not available for all 571 supported devices. The versions based on Android 4.4 KitKat and 5.0 and 5.1 Lollipop are also still supported.

The ROM’s main advantages compared to the “stock” Android and AOSP supplied by device vendors or Google include screen calibration possibilities, advanced gesture support, app-level permission control, sound and interface customisation, button actions assigning, and much more.

Over the years, CyanogenMod has seen a number of controversies, connected first of all to its commercialisation, as well as to the actions of Cyanogen himself. In 2011, Kondik joined Samsung as a software engineer, but kept working on his Android ROM in his spare time. In March 2013, he left the Korean tech giant.

Nearly half a year later, Kondik announced that he had raised $7 million in venture funding for his new company, Cyanogen Inc. The announcement was followed by a lively discussion within the CyanogenMod developers’ community, some members of which thought that their volunteer work had been used by Kondik to make profits. They were also concerned that the source code of CyanogenMod could be closed, which never happened in the end.

What did happen, was that a number of contracts with phone manufacturers were won by CyanogenMod. Among the smartphone models shipped with the CyanogenMod OS were Oppo N1, OnePlus One, Wileyfox Swift and Storm, Alcatel Onetouch Hero 2+, Yu Yureka, and many more.

Cyanogen Inc. has recently gone through a significant staff cut, in which “roughly 30 out of the 136 people” it employed were laid off. There are rumours on the market that the commercialisation of the OS has proven to be less lucrative than expected, and chances are that soon CyanogenMod will be developed exclusively by community volunteers again.

The firmware is distributed under the double licence—Apache License 2 and GNU GPL v2—which allows use and distribution of the software without closing the source. Like many other ROMs, CyanogenMod used to be distributed with pre-installed Google-made apps like Gmail, Search, YouTube, etc. This is no longer the case, however, as in 2009 the corporation reminded the developers that these apps aren’t licensed for free distribution. Users are still able to install these apps separately, of course.

In addition to that, CyanogenMod uses a number of proprietary device drivers in order to support certain smartphone and tablet models, which could potentially be a source of legal issues. No hardware vendor has officially protested against this over the past seven years, however. One of the other custom ROM distributions—Replicant—has removed all proprietary drivers from the code base, and currently supports only a few devices.

If you are looking for the help with customization of your own build of Embedded Android that was built from AOSP or any other open-source version just let us know.

AOKP

The name Android Open Kang Project (AOKP), a wordplay on AOSP, began as a joke when the project started in 2011, but seems to have stuck. The word “kang” is often used by developers and means stolen code, which, of course, has nothing to do with this custom firmware.

AOKP is a lightweight ROM that allows more customisation than the “vanilla” option, including custom toggles, advanced LED control, gesture-controlled shortcuts, vibration patterns, application-level permission control, and CPU overclocking.

AOKP’s original creator Roman Birg joined Cyanogen in early 2014, which led to a significant slowdown in firmware development. “Team Kang” wasn’t active at all in 2015, which is why there’s no AOKP ROM based on Android 5.x.

Things changed in 2016, however. A few new faces appeared in the development community, while Birg himself was also reportedly involved in it again. The current version of AOKP, which is based on CyanogenMod 13, is built upon Android 6.0 Marshmallow. The ROM lists about 90 supported devices, some of which are rather different versions of one smartphone or tablet. More than 3.5 million devices were running AOKP as of 2013.

AOKP is distributed under the same licences that cover Android UI (Apache Licence 2) and Linux kernel (GNU GPL v2), which do not limit the use of the firmware in commercial devices, provided the original source code is available for end users to see.

The AOKP custom ROM’s code base is hosted on GitHub, where everyone is allowed to check it out, make changes and submit a pull request. There’s also a voting system in place that helps the community to highlight the most important changes and patches.

AOKP is positioned as an aftermarket ROM for end users of smartphones and tablets, and hasn’t formed any significant partnerships with device manufacturers. There’s also no way to predict how actively developed the ROM will be in the future, though if you’re interested in its current code base, it’s freely available to take and tinker with.

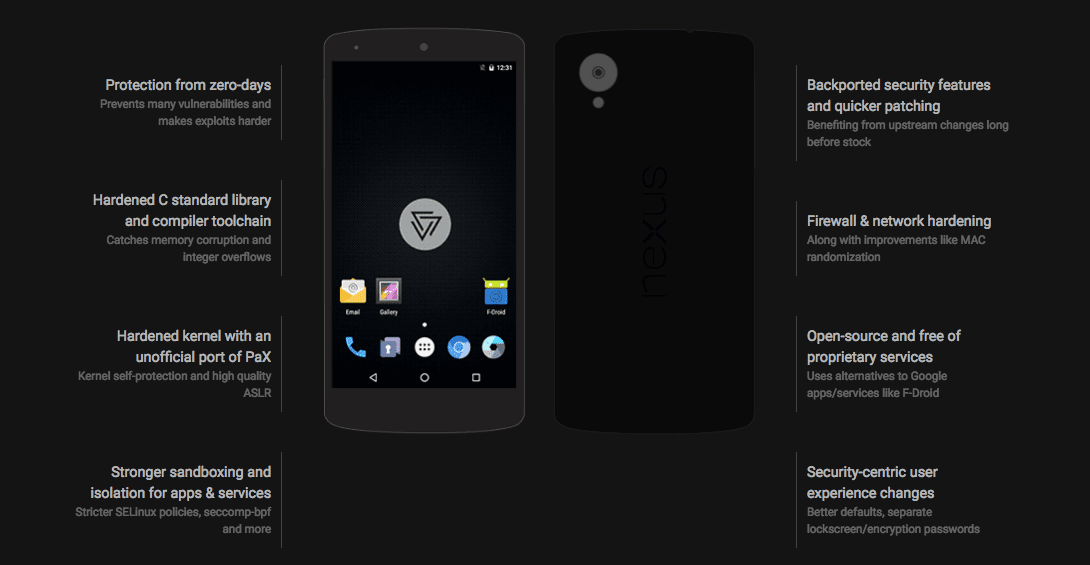

CopperheadOS

Based on the Android Open Source Project, CopperheadOS is a security-focused mobile operating system that currently only supports the smartphones and tablets from the Nexus line. It has been created by Copperhead, a two-man “team of information security researchers, forensic analysts, and software developers” that helps “companies keep their sensitive information locked down.” The company was founded in 2015 and is based in Toronto, Canada.

“Google’s Android security team have accepted many of Copperhead’s patches into their upstream Android Open Source Project (AOSP) code base,” J.M. Porup wrote in his article about the OS for Ars Technica. “But the majority of Copperhead’s security enhancements are not likely ever to reach beyond its small but growing user base, because of performance trade-offs or compatibility issues.”

Initially the project was based on CyanogenMod, though later on the developers changed their minds.

“The initial choice of CyanogenMod as the base for the OS was misguided and burned a lot of development time,” Copperhead co-founder James Donaldson wrote in the company’s blog in March. “The project had to be migrated to the Android Open Source Project as the base, with the ambition of supporting many devices scaled back to the Nexus line. We parted ways with one of our 3 co-founders, leaving us with a bigger burden.”

CopperheadOS brings additional hardening to Android, which includes zero-day exploits protection, enhanced Linux kernel security, stronger sandboxing and isolation of apps, firewall and network security features, etc. Similarly to Replicant, it comes 100 percent free of proprietary software, including hardware drivers and Google apps and services. It also uses an alternative app store, F-Droid, by default.

The source of CopperheadOS can be found in the company’s GitHub repo. The current version is built upon Android 6.0 Marshmallow. The team also offers an extensive technical overview of the changes it has made to the original AOSP code in order to ensure better protection.

Replicant

As we already mentioned, Replicant can be described as CyanogenMod stripped of all proprietary code, which includes hardware drivers. The project was started in 2010 by a team of developers who wanted to create a fully free and pure Android distribution that wouldn’t use proprietary software.

The ROM supports only nine devices, most of which aren’t exactly new. Nevertheless, the ROM seems to be in active development these days, although the current stable version is built upon Android 4.2 Jelly Bean. In a recent blog post, Denis ‘GNUtoo’ Carikli wrote that “Replicant is being updated from Android 4.2 to Android 6.0 by Wolfgang Wiedmeyer.”

Just like most of the other custom Android ROMs, Replicant is distributed under Apache License 2.0 and GNU GPLv2. Its source code is hosted by the Free Software Foundation, which also supports the project financially.

Although not without limitations, Replicant could be a good choice for those looking for a totally free software to run on their hardware with the possibility of adding device drivers where necessary.

OmniROM

Started by a team of Android enthusiasts in 2013, OmniROM is believed to be a community-driven response to the commercialisation of CyanogenMod. As a matter of fact, most of its core developers used to be involved with CyanogenMod before Kondik raised funding for Cyanogen Inc.

The ROM is based on AOSP and offers a multitude of advanced UI customisation features, much like the other firmwares in this overview. It also allows for a number of performance tweaks and CPU fine-tuning. However, arguably the biggest thing that team Omni has achieved is a working multi-window mode, which was first shown in 2014.

“…the argument that ‘nightlies are not for end users’ is over-used, and no longer valid. We’ve found that the vast majority of users want to get nightly updates to their ROM. For that reason, nightlies aren’t a playground – nightlies are for new features that are finished. You should be able to expect the same stability and reliability from a nightly as you would from a “release” ROM, [as well as being able to] report any bugs that prevent this from happening.”

Therefore, it appears that anyone willing to check out the ROM shouldn’t be looking for a “stable” release, but should rather download the latest build available.

Since OmniROM is a pronounced non-commercial project, it still remains a volunteer initiative that lives on donations. No hardware manufacturers have pre-installed the firmware on their devices so far, although the Marshmallow-based version of it was quite popular with the users of OnePlus One.

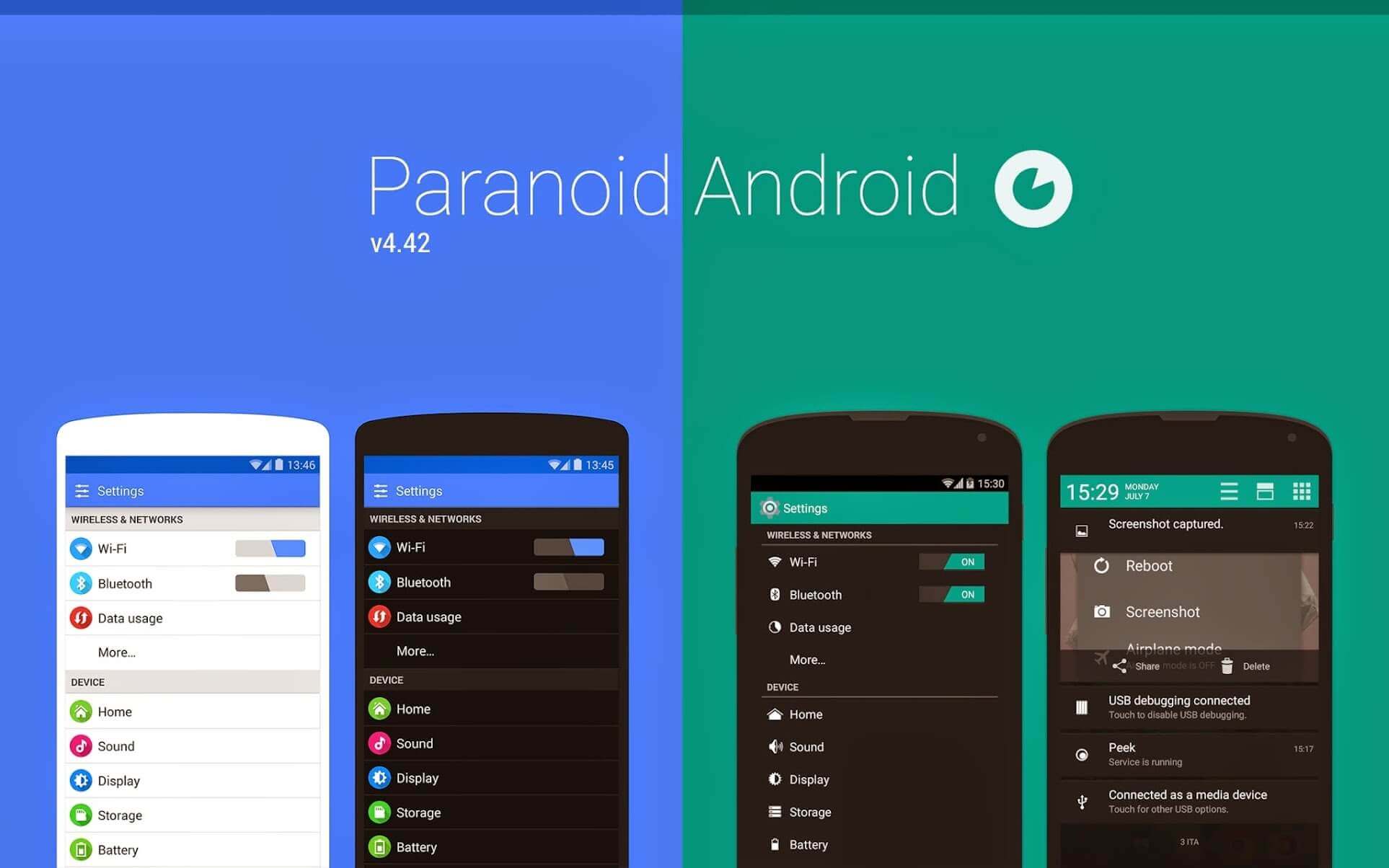

ParanoidAndroid

It sounds quite counter-intuitive, but ParanoidAndroid isn’t focused on security and privacy features at all, but rather enjoys a good rhyme. Nevertheless, in 2015 it was called the second-largest custom Android ROM in the world after CyanogenMod and had more than 200,000 users.

Like many ROMs around, ParanoidAndroid pays attention to advanced customisation, enhanced UI, and performance tweaks. The firmware, however, also has a few features that make it stand out from the crowd. These include the floating mode, a tweak similar to OmniROM’s multi-window mode which allows you to have an app window floating on top of any other app you’re working with.

It also has the so-called “pie controls,” a feature that allows the user to slide from any side of the screen to see a semicircular block of shortcuts to apps and services. This feature is especially useful in the ROM’s “immersive mode” which removes the navigation buttons from the bottom of the screen.

The project was launched in 2011 by Paul Henschel, whose volunteering team worked on the ROM actively until early 2015, when a few key people were poached from there by the phone manufacturer OnePlus. At that time, Oppo-owned OnePlus had had a row with Cyanogen Inc. over licensing in India, and decided to develop its own mobile OS, OxygenOS.

The exodus of a few core developers significantly slowed the pace of Paranoid’s new releases. In October 2015, a news website Android Authority learned that the project was all but put on hold.

“Although [Matt Flaming, one of ParanoidAndroid’s project leads] didn’t have any official statement to share from the team, Flaming relayed to us that the remaining members at PA have become too busy with their lives to continue working on the project,” the story went. “You see, the dev team has always been extremely small, so when everyone seems to have more important things to work on it can be difficult to get work done. Some of the members are focusing on finishing up college and have other important things going on.”

ParanoidAndroid users and admirers were quite pleased, however, when the team announced the ROM’s comeback a couple of months ago. The current version of the firmware is built upon Android 6.0.1 Marshmallow, and some 30 devices are supported.

The source code of the ParanoidAndroid ROM is hosted on Github, available for everyone to tinker with. It’s distributed under the same licences as the Linux kernel and AOSP, which are Apache License 2.0 and GNU GPL v2.

MIUI

This ROM is an aftermarket version of Xiaomi’s Android build that the company pre-installs on its own devices. As of February 2016, the firmware was supported on more than 340 devices, which includes Xiaomi’s own hardware.

Initially, MIUI was based on AOSP and CyanogenMod code base. Its kernel was kept proprietary until October 2013, when it was released on Github in accordance with the requirements of the GPL licence. Two years later, Xiaomi also opened kernel sources for a few of its devices, including the Mi3, Mi4, MiNote and Redmi 1S.

The current version of the ROM—MIUI 7—is based on Android Marshmallow and includes useful features like a special child mode, significantly improved large fonts support, video greetings to use for phone calls, and so on. In addition to this, Xiaomi has just announced that MIUI 8 will roll out to its devices this week, which means that it might soon be backported to other phones and tablets.

Since Xiaomi is a company that works mostly on the Chinese market, where Google’s apps and services are largely banned, it has created a suite of cloud apps of its own, which are included into the firmware. The ROM is now distributed under the double licence common for custom Android firmware—GNU GPL v3 and Apache 2.0.

If you are looking for the help with customization of your own build of Embedded Android that was built from AOSP or any other open-source version just let us know.

Summary

The choice of custom Android firmware builds is getting wider by the day, but it appears that there are still a few core projects which the community is building upon. Going for one of the most popular and actively developed ROMs would be the least risky option, while those interested in more niche features can try out lesser-known options. At the end of the day, there’s always the possibility of talking to the developers to try and work out a solution which is tailor-made for your situation.

Have you already tried to get a custom Android ROM working on your hardware? Share your experience in the comments section!

Illustration by Alina Kropacheva